Huichol Art

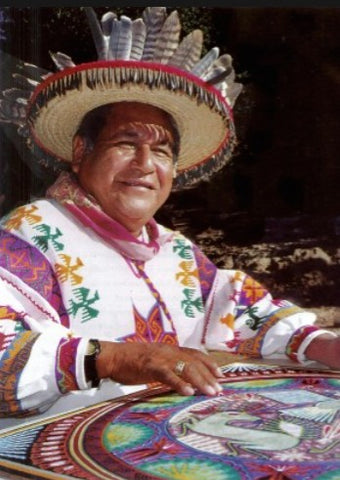

The Huichol Indians live in virtually inaccessible areas of the states of Nayarit and Jalisco, Mexico straddling the Sierra Madre Occidental in an inhospitable region of about 15,000 square miles in scattered kinship settlements.

In the past thirty years, about four thousand Huichols have migrated to cities, primarily Tepic, Nayarit, Guadalajara and Mexico City. It is these "citified' Huichols who, because of the need for money have drawn attention to their rich culture through their art. To preserve the ancient beliefs and ritual ceremonies, they began making detailed and elaborate yarn paintings. The Huichols have only an oral tradition and no written language (thus the many differing spellings of Huichol words).

The first large yarn paintings were exhibited in Guadalajara in 1962, a direct outgrowth of the Nierika - simple and uncomplicated. At present with the availability of a larger spectrum of commercial dyed and synthetic yarn, more finely spun yarn paintings have evolved into high quality works of art. Realism, based on mythology, is the basis of yarn paintings.

Beaded bowls (jicara in Spanish, rakure in Huichol) evolved in this same manner. Beadwork originated as an art form long before the Spanish Conquest of the Indigenous peoples. Instead of the glass seed beads utilized today, bone, clay, coral, jade, pyrite, shell, stone turquoise and seeds were used. These were often colored with insect or vegetable dyes.

Color defines the god or goddess petitioned: for example blue signifies Rapawiyeme (Rapa is the tree of rain); black is Tatei Aramara, the Pacific Ocean, place of the dead, great serpent of rain; red indicates Wirikuta, location of the birthplace of peyote, deer and the eagle. With the development of finer, smaller beads, more detailed work s are now seen, not only on gourds but on wooden jaguars.

Peyote cactus is much revered by the Huichol, a veritable gift from the Gods. Through the use of peyote, the Huichol create the elaborate designs used in their artwork. It symbolizes the essence, the very life, sustenance, health, accomplishment, good fortune of the Huichol. Plus through peyote's hallucinogenic effects, enlightenment and shamanic powers can be achieved. Annual pilgrimages are taken to Wirikuta to collect the peyote. Only the 'purified ones' can participate in the harvest or the peyote will not be found.

Peyote Mandalas or Neakilas (nierika) symbolize the entrance to the spiritual world. As important power objects they are often found at the center of yarn paintings. Each mandala is individual, mirroring peyote vision trances.

Utilizing many of the same sacred designs and patterns as seen in yarn painting and weaving, the Huichol create anklets, bags, belts, bracelets, chokers, earrings and rings with the seed beads. "Life is a constant object of prayer for the Huichol, it is, in the conception, hanging somewhere above them, and must be reached out for," explains Lumholtz, "thus all phases of their lives are prayer - the planting, harvesting, peyote pilgrimages - all art, weaving, bead work, face painting and yarn paintings, embody prayer within symbols.

With this introduction one can better understand the Huichol, their art and their constant communication with the spiritual realm. Ramon Mara Torres sums it all up by observing, "This ancient art, modernized as a result of circumstances entirely outside Huichol culture itself, has become like an exotic flower, eagerly sought after by the conocenti."